On an ordinary day in the 1880's, a Shelbyville, Ohio woman took some dirty dishes and made history. Josephine Garis Cochran was the first person to build a working dish-washing machine, succeeding where others had failed.

Born in 1839, Josephine married a successful merchant in 1858. They entertained frequently, and Josephine grew frustrated that her fine china was chipping. Believing that the cause was harsh handling by those who washed it, she began washing the dishes herself but soon thought there must be a better way to avoid the drudgery of manual washing.

And so Josephine decided to design a dish-washing machine. Circumstances soon gave her a push when, in 1883, her husband passed away, leaving her with little cash and much debt.

Working in a wood shed behind her home, she measured dishes and constructed wire compartments to fit plates, cups and saucers. These were placed inside a wheel that laid flat within a copper boiler. The wheel turned, powered by a motor, and soapy water squirted up over the dishes to clean them. Voila! No more hand washing and the dishes were safe!

On December 28, 1886, Josephine received a patent and began to make her "Cochran Dishwasher" for friends.

Word spread and articles were written. On May 6,1892, the Wichita (Kansas) Daily Eagle wrote, "The patron saint of the emancipated woman of the future will be Josephine Garis Cochran."

But on a large scale, it would take another half century to begin emanicipating most women from manual dishwashing because few homes had water heaters large enough to supply the amount of hot water that the machine required.

Determined, Josephine found a different market. In 1893, she convinced restaurants at the World's Fair in Chicago to use her machine. She also displayed it as an exhibit where it won the highest award for "best mechanical construction, durability and adaptation to its line of work." The publicity drove her invention forward.

Restaurants and hotels, where volume dishwashing - and breakage - were a costly and continuous problem, saw the value of the new machine and began to place orders.

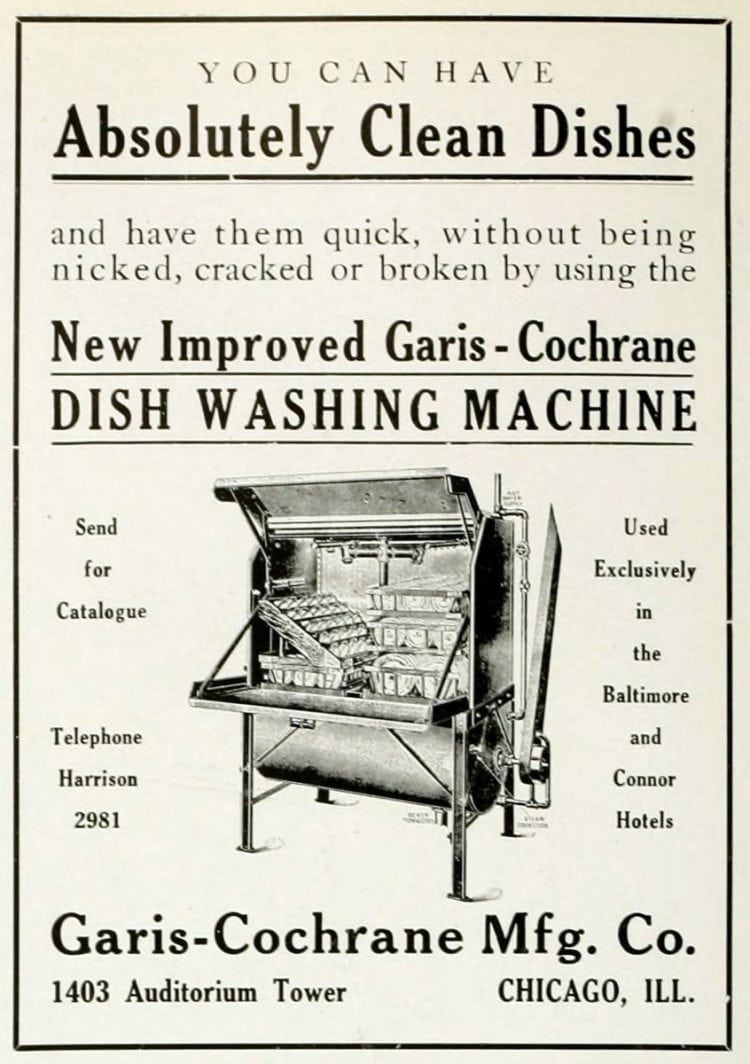

Josephine's growing success led her to open her own factory in an abandoned schoolhouse where, in 1897, production began under the name Garis Cochrane.

Customers extended to hospitals and colleges for whom the sanitizing effects of the hot water rinse were important.

In 1912, at 73 years old, Josephine was still personally selling her machines, just as she had always done. And in the time in which she lived, that was a daunting task for a woman but she never backed down.

After her first sale to a hotel - The Palmer House - in Chicago in 1897, she made a cold call to the Sherman House Hotel in Chicago where she waited for the manager in the ladies' parlor.

Later recounting the experience to a reporter who asked what was the hardest part of getting into business, she answered, "I think, crossing the great lobby of the Sherman House alone. You cannot imagine what it was like in those days for a woman to cross a hotel lobby alone. The lobby seemed a mile wide. I thought I should faint at every step, but I didn't - and I got an $800 order as my reward."

Josephine continued to update her dishwasher design under her death in 1913. Three years later, Hobart Manufacturing Company purchased her company and continued to manufacture dishwashers for commercial use.

In 1919 Hobart formed KitchenAid to produce mixers, its only product until 1949 when it introduced the first KitchenAid dishwasher for home use. The technology was based on Josephine's design. In fact, some of the features that Josephine designed have carried over into modern day equipment.

In 2006 - 93 years after her death - Josephine's contribution was finally recognized when she was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame.

And today, with a simple touch, I turned on my dishwasher and gave Josephine a big thanks.

- Betsy de Parry, VP Marketing and Sales